Table of Contents

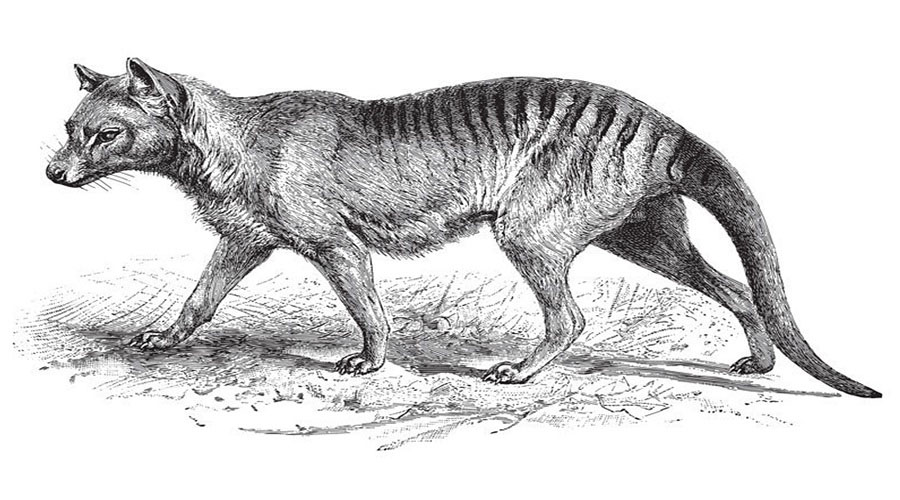

The Thylacine tiger, scientifically known as Thylacinus cynocephalus, was a carnivorous marsupial indigenous to the Australian mainland, as well as the islands of Tasmania and New Guinea. It was commonly referred to as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf.

Unfortunately, the Thylacine became extinct on New Guinea and the mainland of Australia between 3,600-3,200 years ago, prior to any presence of Europeans, potentially due to the introduction of the dingo. The earliest recorded appearance of the dingo also dates back to this time frame, although it never made its way to Tasmania.

Taxonomic and evolutionary history – Tasmanian tiger

At least since 1000 BC, a significant number of thylacine engravings and rock art have been discovered, with petroglyph depictions of the animal being present at the Dampier Rock Art Precinct, which is located on the Burrup Peninsula in Western Australia.

Taxonomic and evolutionary history – Tasmanian tiger

Upon the arrival of the initial European explorers, the aforementioned animal had already perished in mainland Australia and New Guinea, and its presence was scarce in Tasmania. According to historical accounts, Abel Tasman and his team may have had an encounter with the creature in Tasmania as early as 1642, based on their observations of footprints resembling those of a wild animal with tiger-like claws. Furthermore, Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne, who arrived with the Mascarin expedition in 1772, reported sighting a creature referred to as a “tiger cat”.

The initial authoritative sighting of the thylacine occurred on 13 May 1792 when French explorers, under the leadership of d’Entrecasteaux, made note of it in the journal kept by Jacques Labillardière, a naturalist who participated in the expedition. Subsequently, in 1805, William Paterson, the Lieutenant Governor of Tasmania, forwarded a comprehensive depiction of the thylacine for publication in the Sydney Gazette. Moreover, he corresponded with Joseph Banks, providing a description of the creature in a letter dated 30 March 1805.

First detailed scientific description of Tasmanian tiger

In 1808, Tasmania’s Deputy Surveyor-General, George Harris, produced the first detailed scientific description of the thylacine, five years following the European colonization of the island. Harris initially assigned the thylacine to the genus Didelphis, which had been created by Linnaeus for the American opossums, identifying it as Didelphis cynocephala or the “dog-headed opossum”.

First detailed scientific description of Tasmanian tiger

However, recognition of the unique attributes of the Australian marsupials led to the establishment of a modern classification scheme. In 1796, Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire created the genus Dasyurus and subsequently placed the thylacine within it in 1810. To standardize nomenclature, the species name was subsequently changed to cynocephalus.

It wasn’t until 1824 that the thylacine was recognized as a distinct genus, Thylacinus, by Temminck. The common name of the thylacine is derived from its genus name, which is a Greek term for “pouch” or “sack”, modified by the suffix “-ine”, which denotes association or belonging. The pronunciation of the name is “THY-lə-seen” or “THY-lə-syne”. The evolutionary story of the thylacine is an important component of scientific history.

Extinction of Tasmanian tiger

Dying out on the Australian mainland

Around 50-40,000 years ago, during the Quaternary extinction event, Australia experienced a loss of over 90% of its megafauna, except for a limited number of species such as kangaroos, wombats, emus, cassowaries, large goannas, and the thylacine.

Extinction of Tasmanian tiger

Notably, Thylacoleo carnifex, an even larger carnivorous species distantly related to the thylacine, was also among the extinct. Research conducted on this issue in 2010 revealed the potential impact of human activity on the extinction of several species. However, the authors of the research cautioned against accepting a single-factor explanation without proper consideration.

The mainland Australian historical records of the thylacine date back around 3,500 years, and the estimated extinction date closely aligns with that of Tasmanian devils and the earliest records of dingo, which coincided with an intensification of human activity.

According to a study, the possible cause of the thylacine’s extinction in mainland Australia was due to the dingo’s ability to outcompete the thylacine in preying on the Tasmanian nativehen and hunt in packs as compared to the thylacine which was more solitary. The study also revealed that the dingo’s skull could resist greater stresses and pull down larger prey than the thylacine despite having a weaker bite. Being a hypercarnivore, the thylacine was less versatile in its diet than the omnivorous dingo and their ranges overlapped as evidenced by the discovery of thylacine subfossil remains near those of dingoes. Additionally, the thylacine was put under increased pressure due to the adoption of the dingo as a hunting companion by the indigenous people.

According to a study conducted in 2013

While dingoes played a role in the extinction of the thylacine on the mainland, it was primarily caused by major factors such as the rapid growth of human population, technological advancements, and sudden shifts in climate during the period. A report, which was published in the Journal of Biogeography, conducted an analysis of the mitochondrial DNA and radio-carbon dating of thylacine bones. As per the report’s findings, the mainland extinction of thylacine occurred over a relatively short period, which was attributed to climate change.

Dying out on Tasmania

Despite the fact that the thylacine had already become extinct on mainland Australia, it managed to survive until the 1930s on the isolated island of Tasmania, where it was most heavily distributed throughout the northeastern, northwestern, and north-midland regions of the state, with an estimated population of around 5,000.

Dying out on Tasmania

Although sightings of the creature were rare during this time, it gradually gained recognition for attacking sheep, which prompted the implementation of bounty schemes to minimize their proliferation. As early as 1830, the Van Diemen’s Land Company established bounties for thylacines, while the Tasmanian government paid out £1 per adult head and ten shillings for pups between 1888 and 1909. Despite the 2,184 claimed bounties, it is believed that a considerably greater number of thylacines were killed. The unrelenting efforts of bounty hunters and farmers are often credited for the ultimate extinction of this magnificent species.

In addition to persecution, numerous factors significantly contributed to the swift decline and ultimate extinction of the species including competition with indigenous wild dogs introduced by European settlers, loss of habitat, insufficient genetic diversity, decreasing populations of prey, and a disease resembling distemper which afflicted many captive specimens during that era. A 2012 study posited that humans were likely responsible for introducing this illness, which was also present in the wild population and became known as the marsupi-carnivore disease, causing a sharp reduction in lifespan and a considerable increase in pup mortality.

Extinction of Tasmanian tiger

At the onset of the 20th century, the dwindling numbers of thylacines resulted in a surge in demand for captive specimens among zoos worldwide, thereby exacerbating the existing strain on their already limited population. Despite the exportation of breeding pairs, endeavors to breed thylacines in captivity proved unproductive, culminating in the demise of the last thylacine situated outside of Australia at the London Zoo in 1931.

In 1930, a farmer named Wilf Batty from Mawbanna in the northwest region of the state, shot and killed the last known thylacine to be found in the wild. This animal, assumed to be a male, had been observed lingering around Batty’s premises for a period of several weeks.

The thylacine, once classified as an endangered species, lost its status in the 1980s. During that time, international standards stipulated that an animal cannot be considered extinct until 50 years had passed without a confirmed record. Since no definitive evidence of the thylacine’s existence in the wild had been obtained for over 50 years, it met that official criterion, leading to its official declaration as extinct by both the International Union for Conservation of Nature in 1982 and the Tasmanian government in 1986. Consequently, the species was removed from Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in 2013.

De-Extinction: Scientists Say They’ll Bring Back The Tasmanian Tiger In 10 Years

Recently, scientists have expressed a keen interest in resurrecting extinct animals. While the Woolly Mammoth was a subject of fascination not too long ago, today, the focus has shifted to the Tasmanian Tiger. If successful, researchers from Australia and the United States hope to introduce the animal back into the environment, investing multi-million dollars in the project. The last known Tasmanian Tiger, scientifically named thylacine, died out in the 1930s, making this endeavor a significant challenge for those involved.